An abiding memory for a teen fascinated by electronics and radio in the 1970s and 1980s is the proliferation of propaganda stations that covered the shortwave spectrum. Some of them were slightly surreal such as Albania’s Radio Tirana which would proudly inform 1980s Western Europe that every village in the country now possessed a telephone, but most stations were the more mainstream ideological gladiating of Voice of America and Radio Moscow.

It’s a long-gone era as the Cold War is a distant memory and citizens of East and West get their info from the Internet, but perhaps there’s an echo of those times following the invasion of Ukraine. With most external news agencies thrown out of Russia and their websites blocked, international broadcasters are launching new shortwave services to get the news through. Owning a shortwave radio in Russia may once again be a subversive activity. Let’s build one!

Whatever Happened To The Portable Radio?

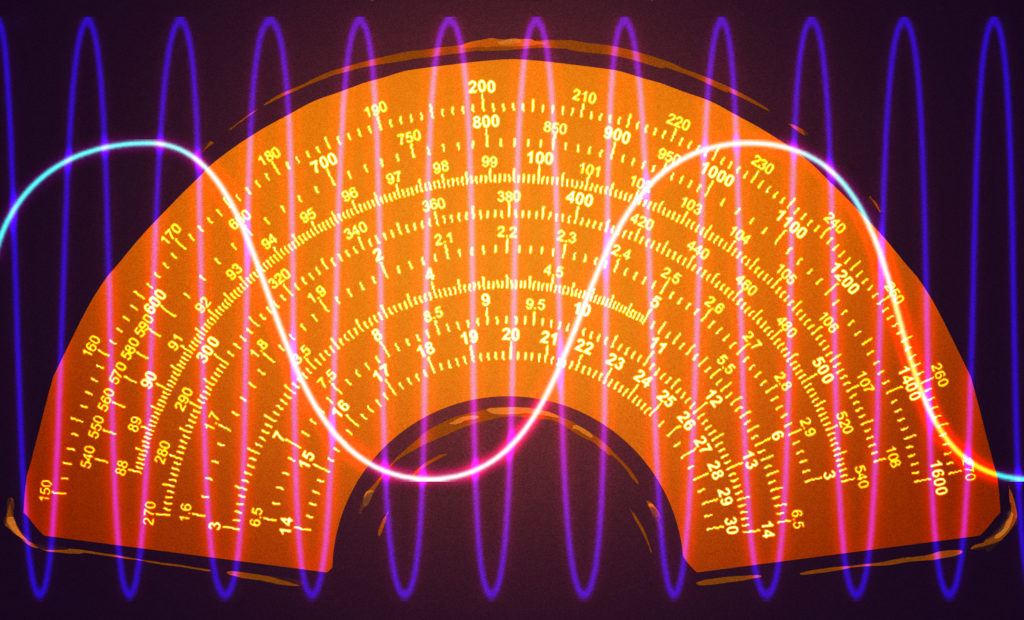

There was a time when everyone had a radio, and radio listening was a universal occupation. From the 1930s families clustered round an ornate family radio to the teenagers of the 1960s and 1970s with their portables, it’s a defining 20th century image. Though many of us still listen to radio here in 2022 the chances are that we no longer do so over AM and certainly not over shortwave. We can get instant access to almost any content online, so it’s by no means certain people will have a radio. If those shortwave transmissions are starting again, how can their intended audience pick them up? Perhaps it’s time to look at shortwave radios with a 2022 slant.

If you lack a shortwave radio and a dig around all your family’s junk hasn’t turned up a relic from decades past, then the simplest way to get one is of course to buy one. AliExpress is full of “world band” radios starting from somewhere under $ 20, and if you don’t mind waiting for shipping from China then it’s the path of least resistance.

But there’s the problem, international events are moving fast and there might not be the luxury of waiting three weeks, or even for that matter of being able to order one at all in a warzone. How can you make one? Yet again there’s an extremely simple option in the Silicon Labs series of one-chip radios. These provide a high-performance shortwave receiver with a minimum of external parts, and really are a miracle of integration. But yet again, in a warzone and in the middle of a chip shortage they just might not be an option. So how can you make a shortwave radio receiver using what parts might be at hand from available consumer electronics? We’ll first be taking a look at some possible avenues, and then introducing a few of the readily available building blocks.

Where Do You Start?

The best way to start is to look at the things you might already have. Such electronic flotsam and jetsam as battery-powered AM radios, car radios, or even $ 10 RTL-SDR sticks. All of these can be modified or converted to receive the shortwave broadcast bands, often with readily available parts.

Probably the simplest method possible might be to directly modify an existing AM radio. I’m indebted to [Phil M6IPX] for passing me on an instructables link for a method to do this. It involves changing the resonant frequency of the ferrite rod antenna coil in the radio, and I’m guessing, relying on a harmonic of the local oscillator father than the fundamental to do the mixing. It doesn’t cover all the broadcast bands, but it might do at a pinch.

The next method lies in converting the shortwave signal from its original frequency to one that can be received by a radio you already have. Radio amateurs will be familiar with the receive converter, a device that mixes the signal from an antenna with a fixed frequency local oscillator to produce an intermediate frequency of their difference, and it should be relatively straightforward to use this technique.

An AM radio tunes in around 1 MHz and can be used with a converter to cover just one of the many shortwave broadcast bands. [Phil] again suggested a 16 MHz crystal oscillator module might be used with a mixer to tune the 15 MHz (19 m) broadcast band onto an AM radio, and a commonly available 4.433 MHz PAL colorburst crystal with a simple transistor oscillator might do the same for the 5 MHz (60 m) band. If I were making such a rough-and-ready converter for an AM radio, I’d try to find a car AM radio to serve as my IF, because these radios are well screened and have a handy co-axial antenna input.

Meanwhile an RTL-SDR can be modified for shortwave reception by either modification or by using a converter. The direct sampling hack bypasses the onboard tuner chip to pipe signals directly to the SDR chip and can be performed by anyone with good SMD soldering skills, and for those unwilling to try it an alternative approach is to use a converter with a 50 MHz oscillator. A few years ago I produced such a converter using a CMOS chip as my entry in the Hackaday Square Inch competition, but there are even simpler circuits to be found.

Finally, perhaps the simplest usable shortwave radio is the direct conversion receiver. Its principle is similar to the receive converter in that the signal from the antenna is mixed with that from an oscillator to yield the difference between the two, and when the local oscillator is the same frequency as the desired station that difference can be fed to an audio amplifier and listened to. It requires three relatively simple circuits in oscillator, mixer, and audio amplifier, and while it doesn’t provide acceptable performance for music radio it’s fine for speech.

The Nitty Gritty: Parts And Circuits

Having fired everyone up about receive converters and direct conversion receivers, it’s time to take a look at those building blocks. How can you make them from the components you’ll find in electronic junk, without ready access to the global electronic parts supply chain?

There are many ways to make oscillators and mixers, but for our purposes the components we are interested in are crystal oscillator modules for the local oscillator, wideband RF transformers for the RF coupling, and diodes as the mixer elements. Variable frequency oscillators are a little more tricky to build but can be made from the most basic of componentsbut if you have a signal generator or even a Raspberry Pi with appropriate software you can use them instead.

Crystal oscillators are ubiquitous on all sorts of PC expansion cards and other computer boards, and provide a logic-level squarewave on their output pin when provided with 5 V. Meanwhile any Fast Ethernet interface will contain an RF transformer, and small signal diodes can be found across multiple different types of electronics. Beyond these parts there may be a need for the normal discrete components such as transistors and passives, but yet again these can be scavenged from a wide variety of sources.

A diode ring mixer is a very straightforward circuit using a pair of RF transformers and four diodes. It works by using the diodes as switches operating at the local oscillator frequency to alternately pass and block the signal frequency. The result is the intermediate frequency (IF), which is the difference between the incoming signal and the local oscillator. It can be very easily made with an Ethernet transformer and four signal diodes using the circuit shown. With a 100 Mbit Ethernet transformer, it should have 100 MHz bandwidth. There are multiple ways in which this circuit can be used with a suitable oscillator as either a receive converter for an AM radio or as a direct conversion receiver.

For the converter, simply connect the output of a crystal oscillator module to the local oscillator pin and feed the output to an AM radio, while for a direct conversion use a variable oscillator and connect the output to a sensitive audio amplifier such as a microphone or phono amplifier. The coupling to the AM radio can either be direct to the antenna socket of a car radio, or via several turns of wire wrapped round the case of a portable AM radio. There is a problem with this circuit in that it has no filtering and thus picks up both both the sum and the difference of local oscillator and IF frequencies, but it should be good enough to pull in a shortwave broadcast.

These are not the only ways to make a working shortwave receiver – after all from a crystal set upwards can be coaxed into working – but we think they are probably the best ways to make one using the electronics likely to be at hand. Maybe you have some ideas to add to the mix? Leave them in the comments!